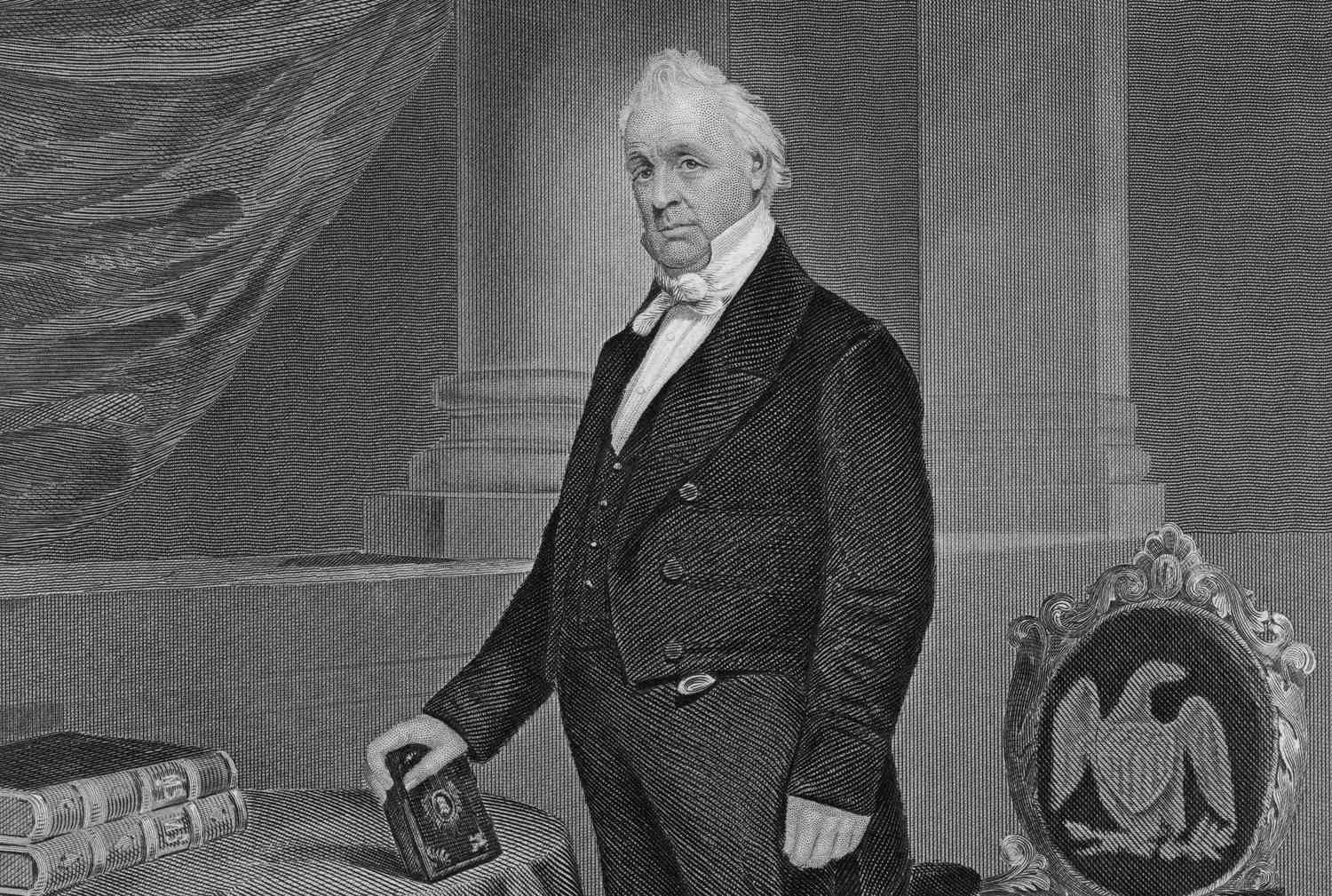

southwold-scene.com – James Buchanan, the 15th President of the United States (1857–1861), presided over one of the most critical periods in American history, as the nation teetered on the edge of civil war. His administration was marked by growing sectional tensions over the issue of slavery, violent clashes between pro- and anti-slavery factions, and the deepening divide between the North and South. Buchanan’s inability to navigate these challenges, coupled with his belief in a strict interpretation of the Constitution and his sympathy for Southern interests, contributed significantly to the disintegration of the Union. By the end of his presidency, the country was on the brink of war, and Buchanan’s failure to prevent the secession of Southern states is often seen as one of the primary reasons for the collapse of the Union.

Early Life and Political Career

James Buchanan was born on April 23, 1791, in Cove Gap, Pennsylvania, to a prosperous Scotch-Irish family. Educated at Dickinson College and later trained as a lawyer, Buchanan began his political career in Pennsylvania’s state legislature before moving on to the national stage.

Diplomatic and Political Experience

Buchanan’s political career spanned several decades and included a variety of important positions. He served as a U.S. representative and senator, as Secretary of State under President James K. Polk, and as the U.S. Minister to the United Kingdom. These roles provided him with significant experience in foreign policy and diplomacy, but his long career in politics left him deeply wedded to the principles of compromise and conciliation, particularly regarding slavery.

Buchanan’s diplomatic experience, combined with his reputation as a Northern Democrat with Southern sympathies, made him an attractive candidate for the presidency in 1856. At a time when the Democratic Party was deeply divided over the issue of slavery, Buchanan’s relative absence from the Kansas-Nebraska controversy allowed him to emerge as a consensus candidate.

The Election of 1856: A Nation Divided

The election of 1856 took place in the shadow of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, a piece of legislation that had reignited the debate over slavery’s expansion into the western territories. The act, which allowed settlers in Kansas and Nebraska to decide whether to permit slavery through popular sovereignty, led to violent conflict between pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions, particularly in Kansas. This period of violence, known as “Bleeding Kansas,” highlighted the nation’s growing sectional divide.

Buchanan’s Victory

In the 1856 election, Buchanan faced Republican candidate John C. Frémont, who opposed the expansion of slavery, and former President Millard Fillmore, the candidate of the nativist American Party (also known as the Know-Nothing Party). Buchanan campaigned as a moderate, positioning himself as someone who could heal the nation’s divisions and restore order.

Buchanan won the election with strong support from the South and key Northern states, but his victory was not overwhelming. He received less than half of the popular vote, and the rise of the Republican Party, which was based on opposition to the expansion of slavery, signaled that the nation was becoming increasingly polarized.

The Slavery Crisis: Dred Scott and Bleeding Kansas

Upon taking office in March 1857, Buchanan faced a nation deeply divided over the issue of slavery. His presidency would be defined by two major events that further inflamed sectional tensions: the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision and the continued violence in Kansas.

The Dred Scott Decision (1857)

Just days after Buchanan’s inauguration, the Supreme Court issued its ruling in the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford. Dred Scott was an enslaved African American man who had sued for his freedom, arguing that he had lived in free territories where slavery was prohibited. The court, led by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, ruled that African Americans, whether enslaved or free, were not citizens and therefore had no right to sue in federal court. The decision also declared that Congress had no authority to prohibit slavery in the territories, effectively invalidating the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had restricted slavery in certain parts of the country.

- Buchanan’s Involvement: It later became clear that Buchanan had played a behind-the-scenes role in the Dred Scott decision. Before his inauguration, Buchanan had contacted members of the Supreme Court, urging them to issue a broad ruling that would settle the slavery question once and for all. However, the decision had the opposite effect, inflaming Northern sentiment against slavery and further polarizing the nation.

- Reaction to the Decision: The Dred Scott decision was celebrated by Southern leaders, who saw it as a vindication of their right to expand slavery into the territories. In the North, however, the ruling was met with outrage. Abolitionists and members of the Republican Party condemned the decision as an attack on free soil and free labor, and it became a rallying point for anti-slavery forces.

Bleeding Kansas and the Lecompton Constitution

Kansas remained a flashpoint throughout Buchanan’s presidency, as pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers continued to clash over whether the territory would allow slavery. In 1857, a pro-slavery faction in Kansas drafted the Lecompton Constitution, which would have allowed slavery in the territory. The document was highly controversial, as it was written without the full participation of anti-slavery settlers, who viewed it as illegitimate.

- Buchanan’s Support for the Lecompton Constitution: Despite the widespread opposition to the Lecompton Constitution in Kansas, Buchanan threw his support behind it, hoping to appease Southern Democrats. He argued that accepting the constitution would bring peace to the territory and help resolve the slavery issue.

- Northern Opposition: Buchanan’s endorsement of the Lecompton Constitution alienated many Northern Democrats, including Senator Stephen A. Douglas, who had championed the principle of popular sovereignty. Douglas argued that the constitution did not reflect the will of the people of Kansas and that it was an affront to democracy. The bitter dispute between Buchanan and Douglas over the issue fractured the Democratic Party and weakened Buchanan’s political standing.

- Outcome: After a series of contentious debates in Congress, the Lecompton Constitution was ultimately rejected by Kansas voters in a fair referendum, and the territory was later admitted to the Union as a free state in 1861. Buchanan’s mishandling of the situation in Kansas, however, further deepened the divisions within the Democratic Party and the nation as a whole.

Economic Turmoil: The Panic of 1857

In addition to the growing sectional crisis, Buchanan’s presidency was also marked by an economic downturn known as the Panic of 1857. The panic was triggered by a combination of factors, including the collapse of several banks, the decline in the price of agricultural commodities, and the failure of key railroad companies.

Buchanan’s Response to the Panic

Buchanan, a firm believer in limited government and laissez-faire economics, took a largely hands-off approach to the crisis. He argued that the federal government should not intervene in the economy and that the panic was a natural part of the business cycle. This approach, however, was deeply unpopular, particularly in the North, where the economic downturn led to widespread unemployment and financial hardship.

- Political Consequences: Buchanan’s failure to address the economic crisis further damaged his political standing, especially in the industrial North. Many Northerners blamed the Democratic Party’s pro-Southern policies for the economic troubles, and the Republican Party gained strength as a result. The Panic of 1857 also exacerbated sectional tensions, as the South’s agricultural economy was less affected by the downturn than the North’s industrial economy.

The Road to Secession: John Brown’s Raid and the Election of 1860

As Buchanan’s presidency progressed, the divide between the North and South grew increasingly unbridgeable. Events such as John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry and the election of 1860 would further escalate the tensions that ultimately led to the secession of Southern states.

John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry (1859)

In October 1859, radical abolitionist John Brown led a raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in an attempt to incite a slave rebellion. Though the raid was quickly suppressed by federal troops, it sent shockwaves throughout the country.

- Southern Reaction: In the South, John Brown’s raid was seen as proof that Northern abolitionists were willing to use violence to end slavery. Southern leaders began to call for increased military preparedness and warned that secession might be necessary to protect their way of life.

- Northern Reaction: While many in the North condemned Brown’s use of violence, others viewed him as a martyr for the cause of abolition. His raid galvanized anti-slavery sentiment and further polarized the nation. Buchanan, for his part, denounced Brown’s actions but did little to address the growing sense of crisis.

The Election of 1860

As Buchanan’s term came to an end, the 1860 presidential election loomed large on the horizon. The Democratic Party was deeply divided over the issue of slavery, with Northern and Southern Democrats unable to agree on a candidate. The party eventually split, with Stephen A. Douglas running as the candidate of the Northern Democrats and John C. Breckinridge, Buchanan’s vice president, running as the candidate of the Southern Democrats.

- Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party: The Republican Party, which had been founded on opposition to the expansion of slavery, nominated Abraham Lincoln as its candidate. Lincoln’s election was seen as a direct threat to the institution of slavery, even though he had pledged not to interfere with slavery in the states where it already existed.

- Southern Secession: Lincoln’s victory in the election of 1860 triggered the secession of Southern states, beginning with South Carolina in December 1860. Buchanan, who believed that secession was illegal but also that the federal government had no authority to stop it, took no decisive action to prevent the disintegration of the Union during the final months of his presidency.

Conclusion: Buchanan’s Legacy and the Path to Civil War

James Buchanan’s presidency is widely regarded as one of the most ineffective in American history, particularly in light of the critical challenges he faced. His failure to take a firm stand on the issue of slavery, his mishandling of events such as the Dred Scott decision and Bleeding Kansas, and his inaction in the face of Southern secession all contributed to the collapse of the Union.

Buchanan’s presidency serves as a stark reminder of how leadership failures during moments of national crisis can have lasting and catastrophic consequences. By the time he left office in March 1861, the country was on the brink of civil war, and Buchanan’s inability to prevent the path to disunion remains a defining feature of his legacy. The Civil War that followed would ultimately resolve the questions that Buchanan had sought to avoid, but at the cost of over 600,000 American lives.